The arboreal realm, a world teeming with life above our heads, holds a particular fascination for those who take the time to look closely. Among its most intriguing inhabitants are spiders, creatures often misunderstood yet incredibly vital to the health of forest ecosystems. While many associate spiders with dark corners or ground-level habitats, a significant number have adapted to thrive exclusively within the branches and leaves of trees. These arboreal acrobats display an astonishing array of hunting techniques, web designs, and survival strategies perfectly tailored to their elevated homes. From the smallest jumping spider to the formidable tarantula, the diversity of tree-dwelling arachnids is immense, each playing a unique role in maintaining ecological balance. This article will delve into the fascinating lives of these canopy dwellers, exploring their adaptations, habits, and the crucial part they play in the intricate web of life.

The arboreal advantage: why trees are prime real estate for spiders

For countless spider species, trees represent more than just a place to perch; they are a multi-story ecosystem offering unparalleled advantages for survival. One of the primary benefits is an abundant and diverse food supply. The foliage and flowers of trees attract a constant stream of insects, from tiny aphids and gnats to larger beetles and moths, all potential prey items for opportunistic spiders. This consistent buffet reduces the effort required for hunting compared to ground-dwelling counterparts who might face scarcer or more unpredictable food sources.

Beyond food, trees offer superior refuge from many ground-level predators. While birds and certain arboreal mammals do pose a threat, the sheer complexity of branches, leaves, and bark provides innumerable hiding spots and escape routes. The elevated position also offers protection from floods and ground-dwelling predators like shrews and lizards that cannot easily ascend. Furthermore, the stable structure of tree branches provides ideal anchor points for constructing intricate webs, which are less likely to be disturbed by larger animals or foot traffic than those built closer to the ground. The elevation also allows for effective dispersal via ballooning, a method where young spiders release silk into the wind to travel to new territories, minimizing competition and extending their range.

Masters of the canopy: common tree-dwelling spider families

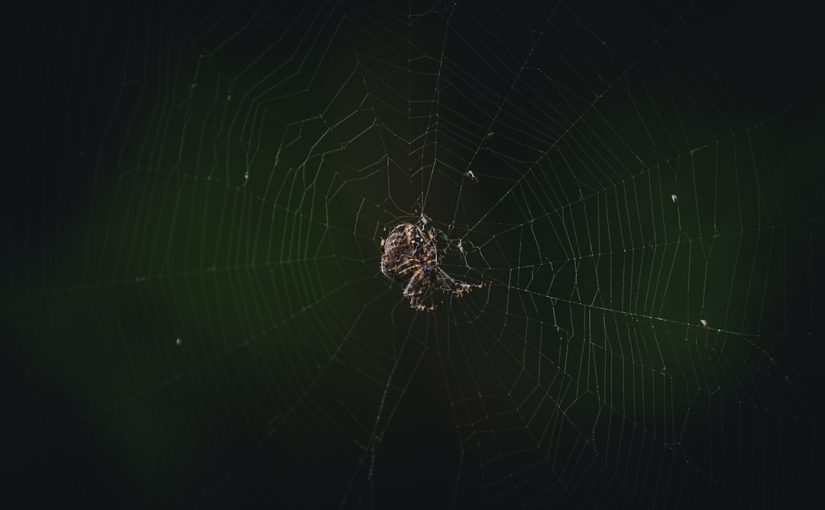

The variety of spiders found in trees is truly remarkable, reflecting a broad spectrum of evolutionary adaptations. Many familiar spider families have representatives that are predominantly arboreal. Orb-weavers, belonging to the family Araneidae, are perhaps the most iconic, constructing their elaborate, spiral-patterned webs between branches to ensnare flying insects. Genera like Argiope and Araneus are common sights in garden trees and forests worldwide.

Jumping spiders (Salticidae) are another highly successful group of arboreal hunters. These diurnal predators possess exceptional eyesight and stalk their prey with cat-like precision, often making impressive leaps from leaf to leaf or branch to branch to ambush insects. Their vibrant colors and often inquisitive nature make them popular subjects for nature enthusiasts. Crab spiders (Thomisidae) frequently inhabit flowers and leaves, camouflaging themselves to ambush pollinators and other insects that visit the blossoms. Their flattened bodies and splayed legs allow them to blend seamlessly with the petals or bark. Less conspicuous, but equally important, are the sac spiders (Clubionidae and others), which often build silken retreats in rolled leaves or under bark flaps, emerging at night to hunt for small insects.

Here is a brief overview of some common tree-dwelling spider types:

| Spider Family/Type | Primary Hunting Strategy | Web Type/Retreat | Common Tree Habitat | Example Genus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orb-weavers (Araneidae) | Web-building (passive trapping) | Large, circular orb webs | Between branches, across gaps | Araneus, Argiope |

| Jumping Spiders (Salticidae) | Active pursuit and ambush | No hunting web, silken retreat for molting/eggs | Leaves, twigs, bark surfaces | Phidippus, Marpissa |

| Crab Spiders (Thomisidae) | Ambush predation (camouflage) | No hunting web, often just sit and wait | Flowers, leaves, bark crevices | Misumena, Xysticus |

| Sac Spiders (Clubionidae, Cheiracanthiidae) | Nocturnal hunting (active pursuit) | Silken sacs or retreats in rolled leaves/bark | Under bark, within curled leaves | Clubiona, Cheiracanthium |

Silk architects: web building and other arboreal adaptations

Silk is the quintessential tool for nearly all spiders, and for tree-dwellers, its utility is expanded even further. The most obvious use is in web construction. Orb-weavers, for example, expertly spin their radial and spiral threads, creating strong yet flexible traps perfectly designed to withstand wind and rain while catching prey. The initial bridge lines of these webs often span impressive distances between branches, a testament to the spider’s engineering prowess and their ability to ‘throw’ silk on the wind to secure distant anchors.

Beyond hunting webs, silk serves numerous other vital functions. Many arboreal spiders construct elaborate silken retreats, or ‘nests,’ within curled leaves, under loose bark, or in branch crevices. These retreats provide safe havens for molting, mating, and most critically, for protecting egg sacs. The silk egg sacs, often meticulously crafted and camouflaged, shield developing spiderlings from predators and environmental extremes. Furthermore, a dragline of silk is a constant companion for many arboreal species. This safety line allows them to quickly drop out of harm’s way when threatened, only to climb back up to their original position. Ballooning, as mentioned earlier, is a remarkable dispersal method primarily employed by juvenile spiders, using long strands of silk to catch air currents and travel to new, less crowded habitats within the arboreal landscape or even across vast distances.

Ecological role and interaction with the arboreal ecosystem

Tree-dwelling spiders are not merely passive residents of the forest; they are active and indispensable components of its ecological machinery. Their most significant role is that of predators, primarily targeting insects. By consuming vast numbers of herbivorous insects, they act as natural pest controllers, helping to regulate populations that could otherwise defoliate trees and damage forest health. This predatory pressure can have cascading effects throughout the food web, influencing plant growth and overall ecosystem stability.

Consider a forest canopy without its spider inhabitants: insect populations would likely skyrocket, leading to increased damage to leaves, wood, and fruits. This would, in turn, affect birds and other animals that feed on these insects or rely on the plants for sustenance. Moreover, spiders themselves become a food source for other creatures. Birds, lizards, and parasitic wasps frequently prey on spiders or their egg sacs, integrating them firmly into the arboreal food web. Their presence indicates a healthy and balanced ecosystem, contributing to the biodiversity and resilience of the forest. Understanding their intricate lives helps us appreciate the delicate balance of nature and the profound impact even the smallest inhabitants can have.

The world of spiders that inhabit trees is far richer and more complex than casual observation might suggest. We’ve explored how trees offer a strategic advantage, providing abundant food and crucial shelter from predators, enabling a diverse range of species to thrive in this elevated environment. From the intricate orb webs of garden spiders to the agile hunts of jumping spiders and the camouflaged ambushes of crab spiders, each family demonstrates unique adaptations to arboreal life. Their mastery of silk, used for everything from elaborate hunting traps to protective retreats and long-distance travel, underscores their incredible ingenuity. Ultimately, these eight-legged residents are more than just fascinating creatures; they are essential ecological engineers. By controlling insect populations and serving as a food source themselves, tree-dwelling spiders play a vital, often unseen, role in maintaining the health and balance of our forests and green spaces. Appreciating their contributions encourages a greater respect for the intricate biodiversity that surrounds us.

Image by: Alfred Kenneally